Civil society

Historically, there is no strong civil society in Ethiopia. First, Ethiopia was ruled for centuries in a feudal system by a monarchy that was replaced in 1974 by the totalitarian military dictatorship. Only since the early 1990’s has civil society been able to slowly develop.

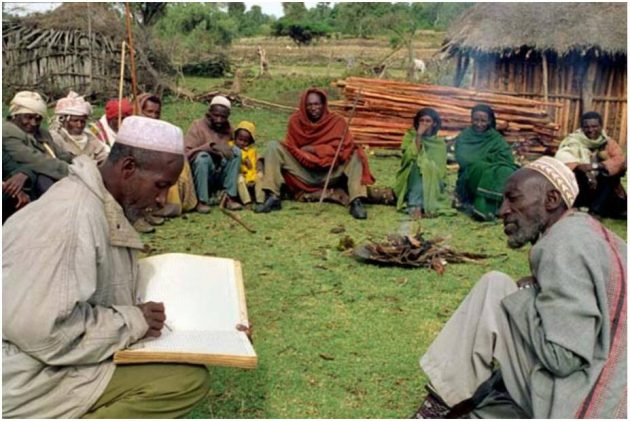

The consistently dominant form of social organization is the family in the broadest sense. In addition, there are traditional institutions such as councils of elders, which often act as conflict resolution bodies. Other traditional forms of civil society organization are also known. The Idir is exemplarycalled: This is a kind of “death fund” into which the members pay. If a death occurs in the member’s family, the funeral will be financed from the common Idir credit. The other Idir members also take on the social obligations associated with the funeral ceremonies (presence, catering for the mourners, etc.). Today, these not-for-profit, voluntary associations also take on many other tasks within the community.

According to countryvv, Ethiopia is a country located in Eastern Africa. Civil society engagement in the western sense, for example in the form of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that participate in political decision-making processes, is not a deeply rooted phenomenon in Ethiopia. The influence – and also the number – of such NGOs have increased significantly in the last 30 years. The largest NGO umbrella organization is the Consortium of Christian Relief and Development Association (CCRDA), which has over 330 member organizations.

The NGO was awarded the Law on Charities and Societies, a new legal framework given. In the run-up, there were violent protests against this legislative proposal together with the international donor community. The main criticism here was that NGOs are considered “foreign organizations” if they receive more than 10% of their income from foreign sources. As a result, these organizations are excluded from working in sensitive areas such as democratization, the rule of law or human rights. However, after minor changes, the law came into force at the beginning of 2009 and led to the fact that some organizations had to stop their work or realign their content.

The Heinrich Böll Foundation decided in late 2012 to withdraw from Ethiopia, because with the new law and the 2011 Regulations came into force implementing a new climax of the restriction of civil society work has been achieved.

In view of escalating anti-government protests in the course of 2016, the Ethiopian government intensified the surveillance of civil society movements and organizations and made their work in some cases considerably more difficult. In addition to waves of arrests in the context of the state of emergency, there were also tightened laws (e.g. a new law on Internet crime). Under Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed seems to be improving the situation for civil society organizations. As part of his dialogue and reconciliation-oriented policy, he has also invited NGOs to discussions and participation in reform processes, and in 2019 he created a new framework with the new Organization of Civil Societies Proclamation created for civil society action in Ethiopia.

Civil society

Human rights

The human rights situation in Ethiopia is unsatisfactory. This applies above all to the rule of law (presentation in court, length of proceedings), the imposition (but not enforcement since 1998) of the death penalty and the obstruction and prosecution of journalists. Arrests are made without an arrest warrant and without a timely judicial review. Very long legal proceedings are common. A completely overwhelmed and overloaded judiciary is responsible for this.

According to Human Rights Watch, the Ethiopian government is using its monopoly in telecommunications and various state-of-the-art technologies not only to spy on well-known opponents or critics in its own country, but also to monitor the normal Ethiopian population and Ethiopians abroad.

The legal requirements for improving human rights are in place. Parliament’s human rights commission has been set up, as has the office of ombudsman. Women’s rights are enshrined in the constitution. However, Ethiopia is far from implementing these legally enshrined human rights: Female genital mutilation and very early marriage are officially prohibited, but remain a reality for many girls and young women. There are indications that the government its anti-terrorism law also makes use of expression and press freedom overturnand silencing opposition members. There are also reports of the political instrumentalization of aid goods by the government and the forced relocation of entire villages for the benefit of foreign investors. The Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation had its human rights practices have to improve Ethiopia prompted.

Media landscape

The media landscape of Ethiopia is dominated by state or pro-government newspapers, radio and television stations.

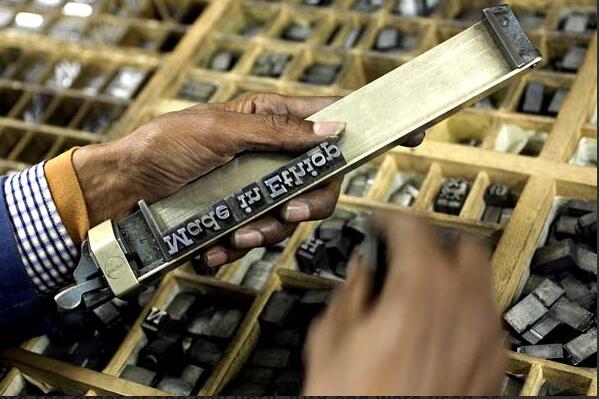

Set of letters in a print shop

Among the numerous newspapers in Ethiopia are some English-language publications. Due to the low literacy rate, however, print media only reach a relatively small part of the population. Radio and television therefore play an important role, especially outside the cities. The state radio broadcasts daily in eight Ethiopian languages as well as in English, French and Arabic. State television (ETV) also has multilingual programs. The state media are operated by the Ethiopian Radio and Television Agency (ERTA) and the Ethiopian Press Agency. There are private radio stations, but only state television stations. Households that are able to use this technology receive mostly Arabic channels via satellite.

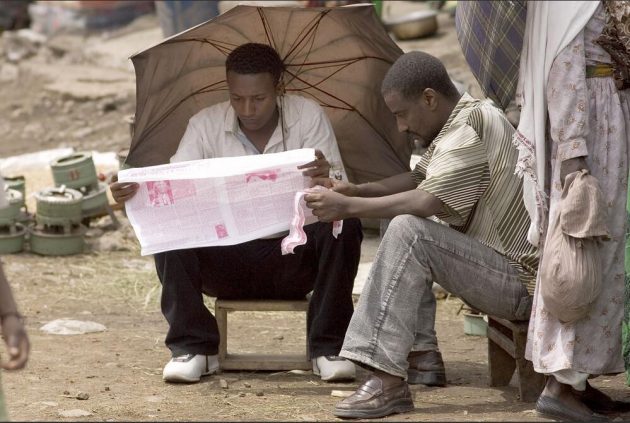

Newspaper readers on the street

With its national-language Ethiopia program, Deutsche Welle is a very respected broadcaster among the population. There have been repeated reports in the past of targeted broadcast interference (so-called jamming) by the Ethiopian government, which also affected the second important international radio station, Voice of America.

Internet censorship and surveillance were the order of the day until 2018 and were used as an important instrument for maintaining power. Since Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed is seeing a clear relaxation in this regard, but free access to the Internet and the monitoring of users are still an issue. For example, news portals available online are repeatedly blocked (temporarily or permanently). Shutting down the Internet in connection with local violent conflicts is also common practice under the new head of government.

For years, press freedom in Ethiopia had steadily declined. For fear of reprisals and arrests, quite a few Ethiopian journalists censored themselves and did not publish on sensitive topics. Private newspapers had repeatedly stopped their publications because the editors had been targeted by the government for their reporting and had subsequently left the country. With the change of government in 2018, the situation has noticeably improved: several hundred previously blocked websites – mostly critical of the government – have now been released, and several well-known journalists have been released from prisons. This is also reflected in theWorldwide Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders. In 2019, Ethiopia ranked 110th out of 180 countries examined – a 40th place better than the previous year. In 2020, the country was able to improve its ranking by a further 11 places up to 99th place.